Updated: 2 January, 2026

Why effective communication in healthcare is taught

Effective communication in healthcare is already well established as a core competency. It appears in accreditation standards, competency frameworks, and learning outcomes across medical, nursing, and allied health education. Learners are taught to listen actively, show empathy, and involve patients in decisions. Yet despite this formal emphasis, communication breakdowns remain common in everyday care.

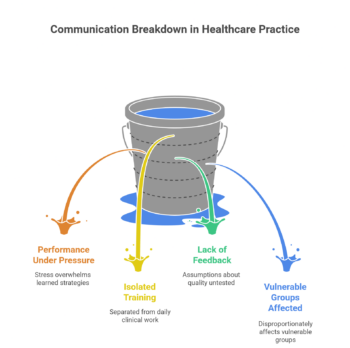

For educators designing curricula, this creates a familiar disconnect. Effective communication in healthcare is clearly defined and assessed in theory, but it often degrades under real-world conditions. Time pressure, emotional load, fragmented teams, and clinical uncertainty all interfere with how clinicians actually communicate with patients and colleagues. As a result, knowing the principles of effective communication does not reliably translate into consistent performance.

This gap persists because communication is not a purely cognitive skill. It is enacted in live interactions, often when stakes are high and conditions are imperfect. When teaching focuses primarily on models or concepts, while real clinical communication remains largely unseen and unreviewed, learning remains fragile.

Rather than revisiting why effective communication in healthcare matters, this blog focuses on why communication training so often fails to embed into practice. It examines how curriculum design, feedback structures, and assessment practices shape whether communication skills develop sustainably over time. In particular, it explores how observation, reflection, and documented feedback create the conditions for communication skills to improve in ways that are both educationally meaningful and institutionally defensible.

Why effective communication does not reliably transfer into practice

One of the central challenges in teaching effective communication in healthcare is that performance changes under pressure. Learners may understand empathy, clarity, and patient-centredness, yet struggle to apply them when conversations become emotionally charged, time-constrained, or ambiguous.

Research helps explain this gap. Street et al. show that communication outcomes depend not only on knowledge, but also on cognitive load, emotional regulation, and situational awareness, all of which fluctuate in real clinical settings. Under stress, clinicians often revert to habitual communication patterns rather than consciously applying learned strategies. Communication does not fail because principles were forgotten, but because conditions overwhelm intention.

Curricula can unintentionally reinforce this problem. Communication training frequently occurs in isolated workshops or simulations, separated from daily clinical work. Learners perform well in structured settings, yet receive little systematic feedback once they return to practice. Without observation, assumptions about communication quality remain untested. Without reflection, insight stays superficial. Without documentation, improvement becomes difficult to track or justify.

This is particularly visible for patients who are older, have limited health literacy, or face language or cognitive barriers. Wynia and Osborn showed that patients with limited health literacy were “28–79% less likely than those with adequate health literacy to report their healthcare organization always provides patient-centered communication,” highlighting how communication failures disproportionately affect vulnerable groups.

For educators, the implication is clear. Teaching the principles of effective communication in healthcare is necessary, but insufficient. Transfer into practice depends on making communication performance visible, reviewable, and discussable over time. Without that infrastructure, even well-designed communication curricula struggle to hold up in real clinical environments.

Reflection and feedback as the missing link

If effective communication in healthcare is taught consistently yet fails to embed reliably, the missing link is rarely more instruction. Instead, it is the absence of structured reflection and feedback on real performance.

Communication skills develop through use, not exposure. Learners improve when they can revisit what actually happened in an interaction, compare intention with impact, and receive targeted feedback. This mechanism aligns with broader evidence on professional learning. A large Cochrane review by Ivers et al. showed that audit and feedback interventions lead to meaningful improvements in professional practice, particularly when feedback is specific, repeated, and linked to observable behavior rather than general advice.

In communication training, this distinction matters. Without observation, feedback tends to rely on self-report or recall, both of which are unreliable under stress. Kurtz and Silverman have long argued that communication skills do not transfer by default because learners rarely receive feedback on how they communicate in real clinical encounters, as opposed to simulated or classroom settings. As a result, learners may understand principles but lack insight into their own habitual patterns.

Reflection plays a critical role here. Research shows that learning after action often has more impact than instruction before action. Delayed, structured reflection reduces defensiveness and allows learners to process emotional and cognitive aspects of difficult conversations. Studies on video-supported reflection demonstrate that reviewing recorded interactions helps learners notice missed cues, nonverbal behavior, and unintended consequences that would otherwise remain invisible (Rammell et al., 2018).

Importantly, reflection alone is not enough. Feedback must be anchored in evidence and revisited over time. Govaerts et al. emphasize that workplace-based assessment becomes more valid and defensible when it relies on multiple observations and documented feedback rather than single impressions. In this sense, feedback infrastructure matters as much as pedagogy. Tools that allow educators to observe, comment, and track communication performance longitudinally enable effective communication in healthcare to be developed as a measurable, trainable skill rather than an aspirational ideal.

What changes when communication becomes visible and reviewable

Making communication visible changes how educators teach it and how learners improve it. When interactions can be reviewed rather than remembered, discussions about communication move from abstract ideals to specific, observable behavior.

For learners, visibility creates insight. Reviewing recorded consultations or handovers helps them see gaps between intention and impact. This matters most for nonverbal cues, pacing, and listening, which patients often notice more clearly than clinicians. Sharkiya et al. show that empathy, listening, and clarity strongly shape patient experience and emotional well-being in older adults, yet clinicians frequently underestimate these elements.

For educators, visibility enables precise feedback. Instead of commenting broadly on “communication skills,” faculty can reference concrete moments, behaviors, and choices. This reduces subjectivity and improves calibration across assessors. Zota et al. found broad agreement among European healthcare professionals that effective communication improves trust, adherence, and satisfaction, while also identifying limited training and feedback structures as persistent barriers. Making communication reviewable directly addresses this gap.

Visibility also strengthens fairness and defensibility. When institutions base assessment decisions on documented observations rather than memory or isolated encounters, they can justify progression and entrustment decisions with greater confidence. This matters particularly for interactions with vulnerable populations. Jenstad et al. show that patients with limited health literacy or communication challenges benefit most from adaptive communication, which requires awareness of what actually occurred.

Finally, visibility supports cultural change. Treating communication as observable work rather than a personal trait makes feedback easier to give and receive. Over time, communication shifts from a “soft skill” to a shared professional responsibility that learners practice, review, and refine with the same rigor applied to other clinical skills.

Designing curricula that embeds effective communication

Curriculum designers embed effective communication in healthcare most effectively when they design for longitudinal practice rather than isolated instruction. Communication skills rarely develop through one-off workshops or single assessment moments. Learners improve when curricula create repeated opportunities to perform in real settings, reflect on what happened, and receive targeted feedback over time.

Effective curricula treat communication as observable work. Research on workplace-based assessment shows that educators make more valid and defensible judgments when they base decisions on multiple observations collected across contexts, particularly for complex skills such as communication and professionalism. Govaerts et al. demonstrate that longitudinal evidence strengthens assessment quality and reduces reliance on subjective impressions. This has a clear design implication: programs should embed communication outcomes across courses, placements, and assessment points instead of confining them to a single module.

Reflection also requires deliberate design. Simply asking learners to “reflect” rarely leads to change unless reflection connects to concrete evidence. Ivers et al. show that feedback improves professional practice most reliably when it remains specific, repeated, and linked to observable behaviour rather than general advice. Educators therefore need to anchor reflection activities to actual interactions, such as recorded consultations, annotated excerpts, or documented handovers, rather than relying on recall alone.

Feedback structure matters as much as feedback quality. Communication skills often fail to transfer because learners receive little systematic feedback once they leave simulated environments. Curricula that succeed define who provides feedback, when it happens, and how educators document it. Clear ownership and predictable workflows prevent communication training from becoming inconsistent or optional.

Design choices also affect equity and defensibility. Wynia and Osborn found that patients with limited health literacy experience patient-centered communication far less often than others. When programs rely on informal observation, these gaps remain invisible. Documented observation and feedback allow educators to identify patterns, intervene early, and justify progression decisions transparently.

Finally, infrastructure supports consistency at scale. Secure tools that enable recording, annotation, and longitudinal feedback help educators operationalise evidence-based communication training without increasing administrative burden. Videolab’s overview of implementing feedback models in healthcare training shows how structured, video-supported workflows make effective communication in healthcare observable, reviewable, and improvable across an entire curriculum.